The Philadelphia Inquirer

Jacobus van Zyl is one of the millions of Americans to join the pandemic economy’s latest trend: quitting your job.

The Glenmoore resident and former financial controller said he had no problem with his previous employer. But when a recruiter from the Robert Half talent agency came calling, he took advantage of a labor market that has empowered workers. He landed a job with a bigger salary, better benefits, and a superior title. He’s now chief financial officer at the King of Prussia-based TNG Consulting.

“There was an ability to further my career,” van Zyl said of switching jobs in May. “The position itself was a big-time improvement for me.”

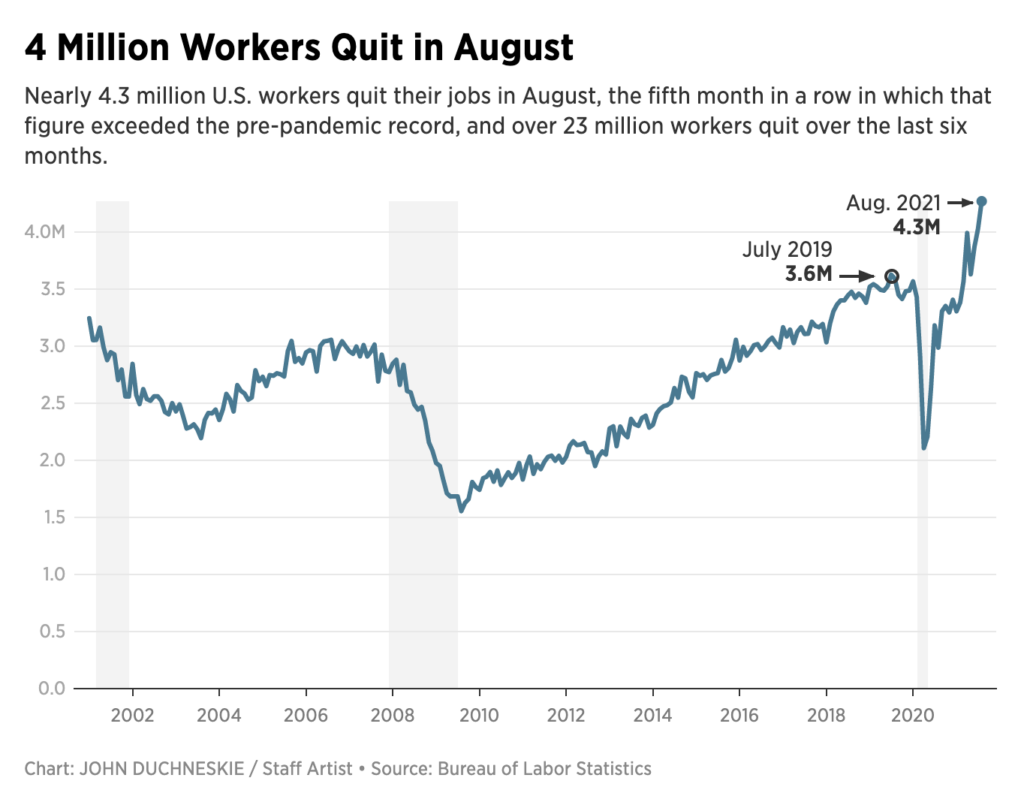

U.S. workers have quit their jobs nearly 20 million times between April and August, 60% more than the same period last year, according to federal data. There were 4.3 million resignations in August alone, the highest monthly total since the Bureau of Labor Statistics started tracking the metric in 2000. The previous record was set in July.

Pennsylvania workers quit their jobs roughly 120,000 times in August, up from 90,000 during the same month last year. That is still below the record high of 130,000, which last occurred in May 2019. In New Jersey, there were 103,000 quits in August, an increase from 69,000 a year earlier. The state record is 110,000, reached in May 2007.

The phenomenon, dubbed “The Great Resignation,” has been fueled by several factors, according to workers, employers, and experts. There was a record number of job openings this summer and employers are paying more to get workers. But it’s not just about chasing money. The pandemic caused many to reflect on what they want from work, such as more flexibility or a different career entirely.

“During this time of stepping off the hamster wheel, so to speak, many of us had epiphanies,” said Mikal Harden, cofounder of Juno Search Partners, a Philadelphia-based talent acquisition firm.

Nearly all of her firm’s clients are dealing with a significant amount of attrition these days, Harden said. The firms winning the battle for talent are offering higher salaries, remote-first work options, and more generous benefits. By contrast, employers that did not support their staffs during the pandemic ran a high risk of losing key players.

“Your employees remembered how you treated them during a global health crisis,” she said.

The wave of resignations is one of several distortions to the U.S. economy brought on by the pandemic. The unemployment rate was 4.8% in September, still above pre-pandemic levels. Yet there were an unusually high 10.4 million job openings in August, the most recent month available.

A July survey from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia suggests employers in the region are responding to the difficulty in attracting and retaining workers. About 74% of manufacturing firms and 51% of non-manufacturing firms said they are offering higher compensation to mitigate the problem, said Ryotaro Tashiro, an economist at the Philly Fed.

Sagefrog Marketing Group, a Doylestown-based business-to-business marketing agency, started awarding quarterly bonuses this year when goals were exceeded, said cofounder and CEO Mark Schmukler. It has raised salaries above the traditional jumps of between 0% and 3%. And the company has implemented a hybrid work model that requires staff in offices only for monthly or quarterly meetings.

“We love our team. We think we have the right people. I am concerned about these macro-market trends,” Schmukler said. “People get [recruiting] calls every day.”

The wide adoption of remote work and the refusal to return to the office are driving many resignations, talent acquisition officials said. Workers who got a glimmer of what life could be like when not tethered to the office don’t want to go back. Companies insisting on a return to the office anyway are paying the price.

“Lifestyle changes have been made. People have learned to accept work from home,” said Sanjay Khatnani, managing partner at J2 Solutions, an information technology staffing firm in King of Prussia. Workers have gotten used to taking their kids to school, working out in the afternoon, or going for a walk with their spouse or partner before doing some more work, he added.

Many Americans have more money in the bank, too, after being holed up at home during the early days in the pandemic and receiving stimulus checks or unemployment benefits. That could be making them more willing to take a chance on switching jobs. The Philly Fed found that fewer consumers were concerned about their finances than they were last year.

“When people are feeling less secure about their financial health they might want to stay with their current employer,” said Tashiro, the Philly Fed economist. But since consumers are generally feeling better about their finances, “people are willing to take risks and seek out other employment opportunities.”

Workers walking out the door don’t always have job offers elsewhere. The West Philadelphia Skills Initiative (WPSI), which trains and connects jobless workers with local employers, has seen more people wanting to quit a job to use its programming, said managing director Cait Garozzo. The workforce development program, run by the nonprofit University City District, has helped some of them land customer service jobs in health care, Garozzo said.

Many of the people coming to WPSI lately have been restaurant workers or gig-economy drivers seeking more career-oriented jobs, she said. Others are simply “done” working those frontline, often low-wage roles after doing them during the pandemic. Indeed, the leisure and hospitality industry had the highest quit rate in August, federal data show.

Workers leaving have come to WPSI saying: “I’m worth more than this. I want something better than this. I want more time for my children,” Garozzo said. “More folks are coming saying that out of the gate, instead of us showing them that.”

For others, the decision to leave a job can hinge on what makes someone happy or feel fulfilled in life. John Bakley, a Mantua resident, worked in casinos and insurance before he found his calling as a teacher at St. Mary’s School in Williamstown. But lately, he questions whether he’s succeeding through remote learning, and wonders if he’d be less stressed doing something else. He said his bosses have been very supportive and are not the cause of the pandemic-related problems he’s faced.

“I don’t know what I’m doing, and I don’t even know if I believe in it,” he said of remote learning. “How do I know that student who’s not even in the same county as me is picking up on the lesson?”

Bakley said he’s thought of quitting dozens if not hundreds of times over the last 19 months. But he believes he will ultimately stick with it. “I’m called to be a teacher,” he said.